Conservationists of Color: April 2022

Conservationists of Color Series Contributors (Concept, Research, and Writing): Mary Spindler, Julia Gasink, and Aaron Kershaw

Our Conservationists of Color series’ April 2022 entry, focuses on two legends in conservation who blazed trails, making a different for people, wildlife, and plant life. Please read their unique and inspiring stories below!

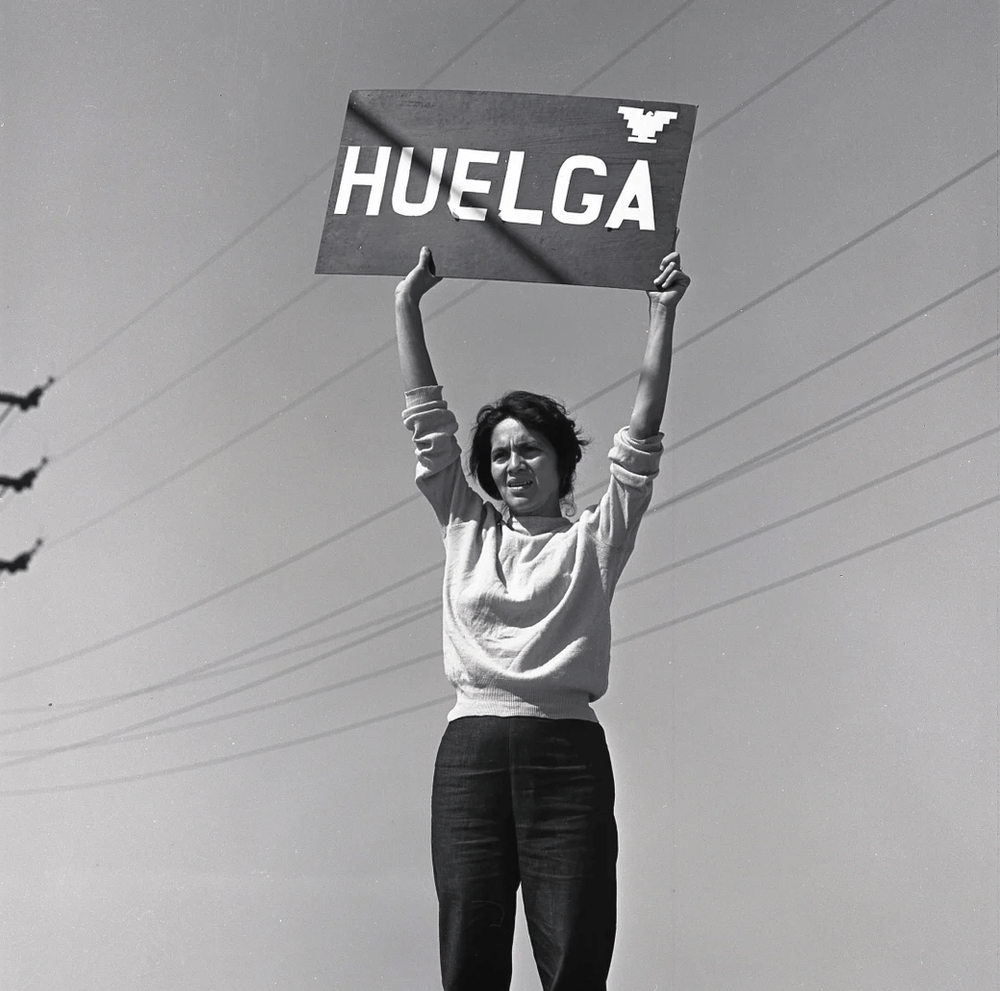

Dolores Huerta

Dolores Huerta is a 91-year-old teacher and farmworker activist who grew up in California’s central valley and witnessed the abundance of food and other vital resources not reach the migrant farmworkers who worked the land. Huerta earned an Associate’s degree in teaching. Still, after seeing her students come to class hungry and without shoes or clean clothes, she decided to help organize the farmworkers to demand improved working conditions and higher wages.

“Si se puede,” or “Yes We Can,” became Huerta’s call to action, inviting the like-minded to advocate for the rights of farmworkers who suffered racial discrimination and unfair and sometimes dangerous labor practices. Huerta’s fight was not all glamour.

In the spirit of the peaceful protest philosophy of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., she was violently assaulted by a SWAT officer, receiving life-threatening injuries, including broken ribs and a shattered spleen. During her career as an activist, Huerta worked alongside Cesar Chavez and served as co-founder of the National Farm Workers Association. Together, their work eventually resulted in the Agricultural Labor Relations Act, Aid for Dependent Families, and disability insurance for farmworkers in California.

Huerta continued her decades-long fight, establishing the Dolores Huerta Foundation for Community Organizing in 2002 after receiving a $100,000 prize from Puffin/Nation for Creative Citizenship. The nonprofit organization inspires and organizes grassroots organizations for environmental and social justice, which only broadened her umbrella of passionate causes.

As the farm industry at times has mistreated its farmworkers, the same went for the land and waters they farmed. Pesticides and poorly designed irrigation systems led to harmful effects on the environment. Huerta thought it essential to protect the farmland and the people who cultivated it by ensuring their work conditions were safe and fairly compensated. Today, many historians attribute the approach of today’s environmental activists to Delores Huerta, and those who know her story believe rightfully so. In 2021, Dolores Huerta was awarded the highest civilian honor in the United States, The Presidential Medal of Freedom.

George Meléndez Wright

George Meléndez Wright was a Salvadorian-American biologist who pioneered wildlife conservation within U.S. National Parks. Meléndez Wright was born in 1904 in San Francisco, California, where he spent his entire childhood. His father, a sea captain from New York, and his mother from El Salvador passed away when he was very young. He was then adopted by his great aunt, Cordelia Ward Wright, who exposed him to the beauty of nature.

Meléndez Wright displayed his love for the natural world and quality leadership very young. By 15, he was a naturalist history instructor at a Boy Scout camp. He had backpacked alone through California’s undeveloped backcountry as a senior in high school and served as the president of the Audubon Club.

By 1925, Meléndez Wright had graduated from the University of California at Berkeley, majoring in Forestry with a minor in Vertebrate Zoology. He soon became the wildlife biologist professor’s assistant at Mt. McKinley National Park in Alaska.

In 1927, Meléndez Wright became one of the first Latinos to join the National Parks Service. His first official assignment was at Yosemite National Park, and he later became the first Latin American to hold a position of authority with the National Park Service.

In 1929, Meléndez Wright created a wildlife biology division and began a wildlife survey of flora and fauna within the parks, which Park Service director Horace Albright approved. The scientific research produced by the program was groundbreaking, finding that conservation and restoration were essential to the wildlife in our National Parks.

With little funding for new projects, Meléndez Wright offered to pay for the entire program out of pocket, clearly demonstrating his convictions. Meléndez Wright’s team published the first Fauna of the National Parks of the United States in 1933. His remarks from the report became the official policy enacted by the National Parks Service.

George Meléndez Wright’s belief that wildlife should not be overly tamed and should remain wild is supported by scientific data, and his efforts make him a trailblazer in the world of conservation. At the height of expanding a Wildlife Division of the National Parks Service, Meléndez Wright died tragically in a car accident. Without his presence, the division received less funding and support but eventually led to the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. This agency works closely with the National Parks Service today.